Corporate Social & Environmental Responsibility – Frequently Asked Questions Click on each question to view (expand) its answer.

-

What environmental impacts of the project on marine life and fish stocks in the Gulf of Aden were anticipated and how have these since been managed?

These impacts have been described in detail in Yemen LNG’s comprehensive Environment and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA), which was published in early 2006. The ESIA provided a detailed synopsis of potential impacts on the environment and local communities. In addition, the ESIA identified a number of clear mitigation measures designed to reduce any potential effects as well as outlining Yemen LNG’s sustainable development programmes which have been designed to leave a positive legacy, both in its operating locality and in the country as a whole. The mitigation measures in the ESIA were subsequently managed through the ESMP (Environmental & Social Management Plan), the first version of which was issued in 2007 for the Construction Phase and the second (current) version was issued for the Operations phase in early 2009.

The primary impacts on marine life and fish stocks can be considered under (1) economic displacement and (2) the marine ecosystem. Whilst these factors are interconnected, each is discussed separately to explain how Yemen LNG has successfully managed this challenge.

-

What measures were taken by Yemen LNG to protect community and environment from any potential impacts associated with the construction of the project?

From the outset of construction in September 2005, Yemen LNG was determined to minimise negative impacts and to leave a positive and sustainable legacy in Yemen. With this in mind, the company produced a comprehensive strategy which encompassed three distinct tiers of action:

- To minimise and mitigate any possible harm or damage to populations, wildlife and the environment, ensuring that any residual impact is negligible or moderate at most

- To provide proper compensation to international standards where any impact cannot be fully mitigated

- To establish a positive and enduring legacy in Yemen to be enjoyed by future generations

The company developed an Environmental and Social Management Plan (ESMP) in order to put this strategy into practice. This comprised a suite of practical plans and procedures ranging from the management of Community Relations to the Management of Water Resources and Hazardous Chemicals. Further details are available in the Social Responsibility section of our website. The original ESMP (published in June 2007) was accepted by the Lending institutions as being fully compliant with IFC and World Bank Group policies and guidelines and it became the cornerstone of the system by which impacts were mitigated and positive processes put in place to leave a sustainable legacy. The original construction phase ESMP was fully updated and revised in March 2009 to recognise the different context of the operational phase (which commenced with first shipment of LNG in November 2009) thus becoming an Operations ESMP. This sets the framework for ensuring minimal environmental impact from the operating plant, whilst building on previous efforts to put in place measures to sustainably improve the livelihoods of people in local communities.

-

How has Yemen LNG compensated for loss of property, land or economic displacement?

As a first step, Yemen LNG has endeavoured to avoid the need for compensation by minimising impacts on people and communities. For example, not a single person has been physically resettled during the 5 years of construction of either the Upstream plant, the main pipeline or the LNG terminal at Balhaf. Nevertheless, a limited amount of short term and permanent economic displacement has occurred to both land users and fishermen, for example in building the pipeline right of way and in constructing the LNG plant at Balhaf. Compensation takes three separate forms, depending upon the nature of the impact. Firstly, for permanent loss of access to land (eg cultivatable or habitable land in the pipeline restricted zone) a system of Land Compensation was developed in which a Government appointed Land Compensation Committee (LCC) reviewed and approved land compensation claims, the funds to be provided from Yemen LNG (disbursed by Government) in accordance with an agreed formula.

Secondly, a number of measures were put in place to deal with short term economic loss (STEL) impacts caused by pipeline and LNG plant construction. These were designed to address specific cases and they were evaluated, managed and settled directly by Yemen LNG. Examples are discussed in more detail under “Community Relations Overview” but they include matters such as; temporary loss of access to cultivatable land, dust and temporary disruption, impacts on beekeeping and honey production, redirection of waterways and access roads and temporary loss of vegetation and crop production. Compensation was arranged either by means of cash compensation (informed by inputs from specialists in the field, such as agronomists) or by the implementation of community projects to improve facilities and infrastructure (eg schools, access roads, planting of elb trees etc).

Thirdly, a suite of measures has been implemented to address the economic displacement of fishermen when access to the fishing grounds close to Balhaf, and access to the landing area on Balhaf beach was restricted and ultimately prohibited. This comprises both cash compensation (managed by the Authorities but funded by the Company) and a holistic set of sustainable development and impact offset projects (eg Fish Aggregation Devices, access roads to auctions, Gela’ah breakwater) which are discussed elsewhere on this website.

-

What measures were taken to protect the marine ecosystem, eg the coral colonies during construction?

From the conceptual phase of the project in 1997, Yemen LNG was aware of a sensitive marine ecosystem along the coastline around, and to the East of, Balhaf cape. An initial environmental baseline study in 1997 evaluated this and then, following project sanction on 26 August 2005, a thorough environmental assessment of the ecosystem in Balhaf bay was performed in September 2005 by marine biologists, which included a detailed description of fish and coral communities and an outline of the potential impacts of the project on these communities. In light of this, a multi-layer strategy was set in place to mitigate impacts. This included; changes to plant design, improved working practices and innovative solutions to particular challenges. Finally, a robust and regular monitoring regime was implemented to monitor the health of the coral colonies and the fish communities during the 5 years of construction.

The plant design underwent several modifications in order to avoid impacts to areas populated by sensitive coral reefs and a number of mitigation measures were taken. These included, but were not limited to:

- Relocating the Marine Offloading Facility (MOF) and harbour to avoid the more sensitive coral areas

- Redesigning the shore protection structure to minimise impacts on corals

- Constructing the first section of the MOF in the form of a bridge to ensure continuous water circulation on either side of the harbour wall and to reduce the “footprint”

- Installing silt curtains to act as a shield ensuring that dust and particles resulting from the construction of the harbour did not reach the surrounding corals

Regular monitoring surveys have been conducted to detect any changes that may occur within the coral community during construction or operation, and to allow appropriate response actions to be taken to mitigate impacts. This monitoring is being conducted by the internationally recognised company (Creocean) and by the Hadhramout University of Science and Technology (HUST).

-

What was the Coral Transplantation Project and why was it necessary?

Despite the effectiveness of the previously mentioned measures, certain aspects of construction (eg the trenching of the seawater intake pipeline) would cause direct loss of corals, unless a solution could be found. Yemen LNG looked at a number of possible solutions, but the one which offered the greatest potential benefit, but accompanied by a high level of ecological risk, was coral transplantation (otherwise known as coral resettlement). This technique, in which individual coral colonies are carefully removed from their natural habitat on the seabed, and relocated to a new habitat, has been tried on a limited scale and with mixed success around the World, but Yemen LNG was to take this technique to a scale and complexity never before attempted.

Corals are fragile species which are easily stressed. Removing them from their natural habitat and shipping them to new locations was sure to be a significant stressor. Survival rates below 50% were mentioned and the technique favoured low numbers of small (young) colonies. YLNG was dealing with large numbers of massive colonies (up to 4 tonnes in weight and some over 500 years old) and the reputational and financial implications of failure meant that a 90-95% survival rate was the target. Nevertheless YLNG believed that this new technique had merit and steps were taken to work with expert marine biologists to increase the chances of success. The idea was to combine scientific knowledge with industrial enterprise and to take this idea from small scale concept to large scale execution.

The risks were extremely high but, conversely, so were the potential benefits. We commenced with small scale trials using marine scientists with a proven track record in coral transplantation. However in late 2006, the pressure of marine construction works demanded a step change in progress. We had to urgently clear the area designated for the intake pipe and move sensitive corals to a safe location within the site perimeter.

In January 2007 we took the decision to implement a coral transplantation programme on a scale never previously attempted. In the first mission, some 600 colonies were transplanted. This was followed by a second transplantation mission in April 2007 which included an additional 400 corals including one weighing 3 tonnes. By September 2007 this project had involved four missions in different locations, it has transplanted a total of 1,500 colonies and it has broken the World Record for successfully transplanting a single massive coral weighing 4,000kg. In January 2007 we took the decision to implement a coral transplantation programme on a scale never previously attempted. In the first mission, some 600 colonies were transplanted. This was followed by a second transplantation mission in April 2007 which included an additional 400 corals including one weighing 3 tonnes. By September 2007 this project had involved four missions in different locations, it has transplanted a total of 1,500 colonies and it has broken the World Record for successfully transplanting a single massive coral weighing 4,000kg.

The overall survival rate is typically in excess of 80% which is much better than other (smaller) missions around the World where a survival rate of 0% to 70% is typical. Furthermore, many important lessons have been learned about transplantation protocols and this has moved the knowledge of this new technique forward considerably. The future prognosis is good.

YLNG faced a significant challenge in building an LNG terminal in an area of outstanding natural biodiversity. The construction schedule demanded quick, firm and decisive action. The pressures from external stakeholders were intense but the decision to implement an innovative and daring programme of coral transplantation has proven to be the correct one. Monitoring is demonstrating the success of this technique and it is a model which from which other projects could usefully learn.

-

Is warm water from the LNG plant outfall harming marine life or corals?

Corals are by their very nature, very sensitive to changes in their natural habitat. Water temperature increases can be particularly damaging as they can result in “bleaching” in which the coral becomes stressed, turns white and dies. This was evidenced during the Worldwide coral bleaching event known as “El Nino” the worst of which occurred in 1998 in which there was a dramatic reduction in reef coverage worldwide. Yemen LNG was cognisant of this risk, particularly in the area around the seawater outfall pipe which is bounded on both sides by coral colonies. Warmer seawater from the plant cooling system outfall is ejected in this area and it mixes with the natural seawater.

In order to analyse the effect of this phenomenon, Yemen LNG commissioned Sogreah to undertake 3-dimensional thermal modelling studies to model the movement of warm water under different environmental conditions. The results of these studies suggested that a reorientation and extension of length of the outfall pipe would be of benefit, the coral colonies being located inshore in shallow water. This was accepted and the appropriate design changes implemented. Yemen LNG set a limit of a 10C temperature rise at the coral banks, under maximum plant thermal conditions, in order to avoid any negative impacts.

In order to verify actual performance during plant operations, a suite of thermal data loggers have been placed at various points in the sea around the outfall pipe and the coral colonies. These continuously record seawater temperature and the data is downloaded and studied on a regular basis. This not only verifies that the criterion of a 10C temperature rise at the coral banks is being complied with, but it provides a new insight into the natural changes in seawater temperature in this area, thus adding to the scientific knowledge of how corals behave in changing climatic conditions. The regular coral health monitoring programme mentioned earlier supports this work and it is showing that the corals in and around Balhaf are particularly “resilient” to external stressors, perhaps explaining the unusual richness and diversity of the Balhaf corals.

-

What role does IUCN play in the Yemen LNG Project?

In 2008, Yemen LNG entered into a three year co-operation agreement with the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) a non-profit organisation based in Geneva, which is highly respected for both its scientific integrity and its independence. The idea of this agreement was to invite IUCN, through a series of reviews, missions and interventions, to independently evaluate the effectiveness of the implementation of Yemen LNG’s biodiversity action plan (BAP) through which actions are taken to both minimise impacts on the natural ecosystem and to maximise benefits eg through training, capacity building, infrastructure development etc.

IUCN employs a team of six internationally recognised scientists, each with expertise in a specific area (eg fisheries, coral reef ecology, coastal zone management) and reviews are carried out every six months. This not only brings a valuable and independent insight into the work which Yemen LNG is doing to manage terrestrial and marine biodiversity, but it highlights areas for improvement and change by tapping into contemporary scientific knowledge at its highest level.

-

Why was it necessary to prohibit fishing in the Maritime Exclusion Zone and Maritime Restricted Area and what are the effects?

The primary rationale for creating the Maritime Exclusion Zone (MEZ) in which all fishing is prohibited, was to provide a safe and secure entry and exit point for the LNG tankers and thus not pose a threat to the much smaller fishing boats. There is also a Maritime Restricted Area (MRA) around the MEZ but fishing boats are allowed to transit this area when tankers are not present, although they cannot stop and fish in the MRA.

This has the negative effect on local fishermen of prohibiting access to Balhaf beach (where prior to November 2005 boats landed their catches during the monsoon season) and it prohibits access to the inshore fishing grounds in the immediate vicinity of Balhaf (ie in the area bounded by the MRA).

Nevertheless there is a very strong benefit to this prohibition which is based on the fact that a “no-take zone” has been created in an area in which fish spawning takes place. Prior to 2005 there was strong evidence (through studies and data collection) of overfishing in this area. The local fishermen, in trying to reduce non-productive sailing time and fuel costs, tended to fish inshore where the spawning areas were located. This resulted in gradual depletion of fish stocks, a situation which scientists felt was becoming irreversible.

The no-take zone has reversed this trend by protecting the fish spawning area and thus allowing the fish to grow to maturity and spawn without the threat of being captured too early in their gestation. However, whilst this (of itself) benefits and protects fish stocks, it does not help the economic displacement of the local fishermen. As such, additional measures had to be taken to offset the economic displacement of the local fishermen, as studies undertaken by Macalister Elliott & Partners (MEP) had shown that artisanal fishing was the main economy in this Region and any reduction in earnings could be serious. These measures included; cash compensation to offset short term economic loss, the installation of Fish Aggregation Devices, and the construction of a new breakwater at Gela’ah. The outcome of all of the various measures has been that by the end of 2010, studies by MEP based on data monitoring through the local fish auctions showed that (i) the fish catches were higher than prior to 2005 and (ii) economic displacement had been reversed, following the “dip” predicted in 2006-2008 whilst the various measures took effect. This demonstrates the sustainability of the local fishing industry and the benefits of the no-take zone.

-

How have the local fishermen in Balhaf been compensated?

The construction of the LNG plant at Balhaf resulted in the displacement of some of the traditional fishing activities in the bay. In order to inform mitigation planning and to support local consultation of fishermen, Yemen LNG commissioned McAlister Elliott and Partners, a specialist fisheries consultancy with experience in Yemen, to undertake a number of studies (carried out in December 2005) on the potential impacts to local fisheries and their recommendations for local compensation measures. The fisheries study suggested a number of options for short-term and long-term compensation measures which would benefit all of the communities of Al’Ayn Bay, including Gela’ah, the fishing community closest to Balhaf, and Bir Ali, the nearest fishing centre to the east. The proposed measures were designed to reduce the costs of fishing, increase the value of the fish to the local fishermen of their landed catch and facilitate in the longer term private sector investment in the area, as well as offer additional employment in fisheries services. The project will also be making a major contribution to Yemen’s Coastal Zone Management Plan (CZMP), which includes sustainable fishing measures. Specific compensatory measures included:

- The payment of 450 million YER in cash compensation to offset economic displacement of the fishermen during the period between the commencement of construction and the time at which the community fishing projects became self sustainable.

- Provision of nets, tents and boat hauling equipment.

- Infrastructure development and training to build the capacity of the Ministry of Fish Wealth (MFW)

- Constructing a breakwater in Gela’ah to substitute for the loss of access to Balhaf beach. This can accommodate up to 250 fishing boats, i.e. several times more than the original number of fishing boats that used to fish in Balhaf.

- Installing Fish Aggregation Devices in Al’Ayn Bay to help attract fish, facilitate fishing, and reduce the “catch per unit effort”

- The construction of access roads both in Gela’ah and in Bir Ali (the regional fish market about 30 km east of Balhaf) to the local fish auctions, and the provision of computers and training for better monitoring of prices and catches.

-

What were the reasons for building the Breakwater at Gela’ah and is it working?

The breakwater structure was designed as an compensatory offset measure to replace the loss of access to Balhaf beach during the monsoon season. Traditionally, a number of local fishermen (anecdotally as many as 200, but evidentially much fewer in the years preceding commencement of site construction) used Balhaf beach as a sheltered landing area, despite the lack of infrastructure there (eg no auction house, no local population).

The breakwater was, following consultation with the Ministry of Fish Wealth and local fishing communities, located at Gela’ah which is the next village east of the Balhaf plant. Gela’ah had limited infrastructure but it was already established as a fishing village. Furthermore there were no coral colonies to disrupt in the construction of a breakwater and the beach at Gela’ah offers a gentle slope which is ideal for landing the small craft favoured by the local fishermen.

The breakwater was designed by Sogreah who had significant previous experience of designing breakwaters around the World. It had two primary design purposes; Firstly to provide a “safe haven” for fishing craft during the monsoon season during which sea conditions can be quite difficult for small craft attempting to land fish. Secondly, the “three section” design of the breakwater would encourage the formation of 3 “tombolas” due to a change in the beach profile. This would facilitate the landing of small craft during the monsoon.

It is now almost five years since construction was completed and the beach profile is changing much as predicted by Sogreah in 2005. However, an unexpected third benefit is becoming apparent. The rocky construction of the breakwater sections is acting as an artificial reef and studies by scientists have discovered that it is acting as a haven for shellfish (eg shrimps and lobsters). These are a valued resource and they are further evidence of the sustainability of the marine ecosystem post-construction.

-

What are the benefits of Fish Aggregation Devices?

Fish aggregation devices (FADs) are simple moored floating structures which capitalise on a phenomenon whereby fish are attracted to objects which float on the surface of the sea. As such, fish aggregation devices do not actually increase fish stocks, but their advantage is that (1) they relocate the areas in which fish gather and (2) by so doing they can reduce what is known as the “catch per unit effort” which is the cost of fishing (time, fuel, distance).

Prior to the Yemen LNG project, FADs had never been installed in Yemeni waters. Initially, 3 FADs were deployed in 2007 on a trial basis. Based on the success of these 3 pilot project Fish Aggregation Devices, nine more FADs as part of the FADs Phase 2 (4 in July 2010 and 5 in August 2010) were deployed by MacAlister Elliott & Partners (MEP) thus twelve altogether by the end of 2010. However, there were ongoing technical difficulties (including chafing of some of the ropes due to a depth problem and instability of some buoys) and at the end of December 2010 only 5 FADs were functional, with 7 having to be redeployed. Although capacity building has been undertaken to empower local fishermen to understand the components of the FADs as well as how the FADs are being deployed, the challenge for cooperatives/fishermen to take ownership of the maintenance and management of FADs deployed by Yemen LNG remain which will be addressed through further capacity building, training and financial support from Yemen LNG. Fishermen however showed interest in constructing and deploying their own community FAD (which started at the end of 2010) which is evidence of the financial benefits of the FADs as well as successful knowledge transfer by Yemen LNG and therefore also an indicator of sustainability.

Despite difficulties encountered, the FADs project has proved to be Yemen LNG’s most successful economic project. Data collection and analyses has shown that fish caught at the FADs have increased fishermen’s income with US$10m over a period of 3 years (MEP, 2010).

-

Has the beekeeping/honey programme met expectations?

Yes the overall objectives of the SD Beekeeping program since 2008 have been achieved. Previous difficulties during the development of the Apiculture SD projects during 2008 and 2009 have been largely overcome during 2010 largely due to 100% targeted beekeepers who have been trained; improved expectation management; technical difficulties related to planting of Elb trees that have been overcome with improved understanding of the importance of immediate tree care and pest issues; difficulties with irrigation that are better understood and addressed and clarification of ownership and responsibilities resulting in 97% of trees planted in 2010 being in good condition. This is highly significant in terms of sustainability of the apiculture projects.

Overall lessons have been learned from the challenges of the start up processes of this culturally important and economically significant program and successes during 2009 and 2010 and most of the previous difficulties were addressed during the training conducted in the mobile beekeeping schools and the training including the value of wax and its uses, understanding disease and problems and adopting new technologies such as the mobile hive and tree planting techniques. A dedicated SD Project Coordinator, the appointment of a skilled agriculture extension specialist and two dedicated field co-ordinators who directly train and build capacity of the beekeepers as well as the continual process monitoring of the beekeeper’s activities were important contributing factors to the overall success of the SD Beekeeping program. The specialist implementing agents have also been retained for occasional field visits for specific problem solving, project planning developments as well as supporting specialist capacity building during dedicated training sessions.

The basic monitoring indicators demonstrate that beekeepers and farmers are transferring farmer to farmer knowledge, which is a key/significant sustainability indicator. Moreover, mentoring is being used as a tool for keeping the different project aspects on track specifically to ensure the integration of the beekeeping and tree (farming) project aspects. This monitoring is done by the Yemeni field level co-ordinators who have regular meetings and field visits to ensure successful integration, understanding and on the spot problem solving.

-

How do you know that your Sustainable Development strategy is working effectively, efficiently and sustainably?

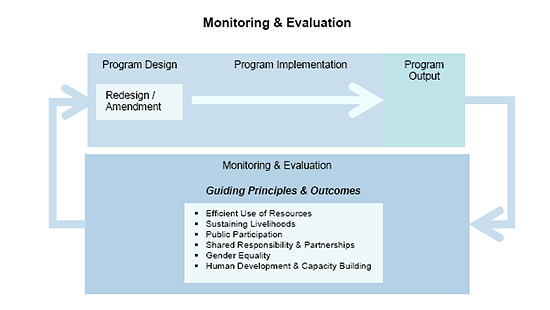

This is achieved through a robust system of Monitoring and Evaluation (M&E). The ESMP states that “Primary monitoring and evaluation responsibility will rest with Yemen LNG. However, for certain elements Yemen LNG will rely heavily on input from external auditors”. During 2010, an internal M&E system for the 3 components of the Social Management Plan was developed and implemented. The M&E system was informed by Yemen LNG’s Environmental and Social Management Plan. A range of indicators have since been developed to support the ongoing monitoring and evaluation of community investment projects, livelihood restoration and reinstatement and the effectiveness of community engagement within the project area. The outcome indicators are assisting in the development of a more robust Social Monitoring and Evaluation (M&E) Framework during 2011 to track process and progress, and to determine whether the social component is making a positive difference (maximizing beneficial project impacts) or minimizing risk (mitigating or reducing the negative impact of project activities as far as practicable).

The M&E framework provides details of what each of the projects will accomplish; how it will be accomplished and how to evaluate whether it has been accomplished. It also determines if:

- goals and objectives are being achieved;

- project design and criteria are being followed;

- implementation effects are occurring as predicted;

- emerging or unanticipated issues are arising;

- projects are efficiently and effectively managed

- lender / social performance review requirements are complied with

- International best practice is followed

- national legislation is adhered to

- human development and capacity building takes place

Components/Indicators contained in the M&E framework (supported by data collection and analyses) include baseline information, objectives, key messages, risks and mitigation measures as well as indicators that are regarded as the ‘Results Chain of a project including inputs, outputs, outcomes and impact indicators (see Figure below).

-

Has Yemen LNG’s mitigation programme been endorsed by the Yemeni authorities?

Yes. The Environmental Protection Authority (EPA) in the Ministry of Water and Environment (MWE) has provided written approval of the Environmental and Social Impact Assessment and mitigation measures (letter dated 5 December 2005). In addition, the Ministry of Oil and Minerals has endorsed the EPA and Ministry of Water and Environment approval.

-

Is Yemen LNG’s Social Compliance programme independently verified?

Yes. An independent and widely experienced social scientist, acting on behalf of the Lending Agencies, has been contracted to undertake four Social Performance Reviews (SPR) at an approximate periodicity of six months. The first 2 reviews were in April and December 2009, the third in December 2010 and the fourth and final review was recently completed in July 2011, the report from which is awaited.

Performance and compliance with the Social Management Plan has improved significantly between SPR1 and SPR4, as staff training and development has become effective and embedded, and the management systems which were evolving through the construction phase of the project have improved both in efficiency and effectiveness of delivery.

The report from SPR3 is available on the website and the report from SPR4 will be made available in due course.

|